When the Numbers Get Worse but the App Feels Faster

Waiting times are down by a third. You would not guess it from the numbers. That is the paradox at the heart of this story.

We like to think performance numbers are simple. Train harder, the scale should drop. Yet anyone who has exercised knows the story is not so neat. You can feel fitter while the numbers move the wrong way. App performance is the same. Sometimes the metrics get worse at the very moment the experience gets better.

That is what happens when we move from many sub-domains to a single domain.

The Old World

For years our products lived apart. Sports, Gaming, Cashier, Account, Promotions. Each sat on its own sub-domain, each with its own lifecycle. When a player moved between them, the app treated it as a fresh start.

Everything was loaded again. Code, images, styles, scripts. On a mid-range device the first load might take eight seconds. Switching to another product triggered the same process, only a little shorter. Three to six seconds on each move before the new screen was ready.

The metric known as Largest Contentful Paint, or LCP, tracked these loads. LCP is simply a measure of how long the app takes to load. Every switch left a footprint. The data matched what players felt: long waits that repeated again and again.

The New World

Now imagine all those sub-domains joined together. Sports, Gaming, Cashier, Account and Promotions under one roof. The player can move between them without starting over.

The result is immediate. Transitions are at least forty percent faster, and in some cases closer to sixty. What once took three to six seconds can often fall to two, sometimes less. The app reuses what is already in memory. The connection stays open. The experience feels smoother and less brittle.

But here the paradox begins. Because those movements are no longer seen as new loads, the metric no longer counts them. Only the very first entry into the app produces an LCP.

The Paradox of Fewer LCPs

By joining the sub-domains together we have stripped out wasted effort. Players are no longer forced through repeated reloads. The transitions are quicker, the experience is better. Yet the metric suggests the opposite.

Why? Because LCP only measures how long the app takes to load. In the old world every switch between sub-domains was counted as another load, so the dataset was full of them: the heavy first entry plus a series of smaller reloads.

In the new world only the first entry is counted. All the later gains, the faster moves between products, vanish from the data. They are erased from view.

That has a strange effect. Before, the heavy first load was softened by the smaller reloads. Averaged together, the number looked manageable. Now there is nothing to balance it. The only figure left is the largest one. On paper the number rises, while in practice the app is faster.

A Quick Example

Numbers vary. They change with devices, networks, and even time of day. But the shape of the story is the same everywhere.

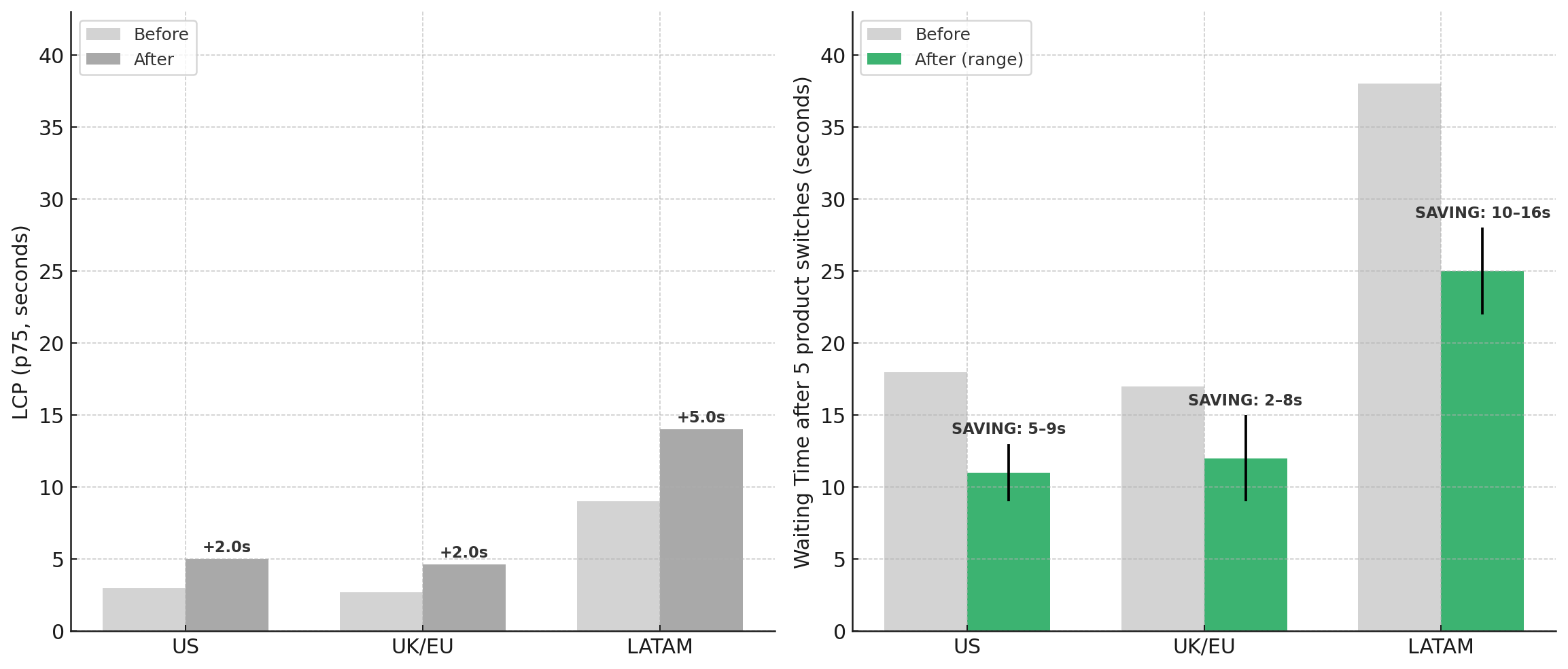

In the old world, the metric was dominated by smaller reloads. In the UK we saw p75 LCP at about 2.7 seconds. In the US it was closer to 3 seconds, and in LATAM around 9 seconds. Those were the figures that made it into the chart because most navigations were short reloads.

After consolidation, only the heavy first load is counted. The chart now shows bigger numbers: in the UK about 4.6 seconds, in the US closer to 5, in LATAM around 13–15. On paper, the app looks slower.

But the total journey is shorter. With five navigations between products, the waiting adds up differently:

- In the US, it fell from roughly 18 seconds to between 9 and 13.

- In the UK and Europe, from about 16–18 seconds to 9–15.

- In LATAM, from about 36–40 seconds to 22–28.

The savings are real: around 4–9 seconds in the US, 5–9 in the UK and Europe, and 8–14 in LATAM. The paradox is simple. The reported LCP goes up, yet the experience is faster and smoother.

Why It Matters

If you only look at the graph, you might believe performance has deteriorated. In truth it has improved. The repeated pauses have been removed. What was once six moments of waiting is now only one.

It is like the difference between a stopping train and a direct service. In the old world, every switch between products was another halt along the way. The train still got you to your destination, but each stop added minutes to the journey.

In the new world, the train leaves once and runs straight through. The departure time on the timetable looks the same, but the arrival is sooner because the intermediate delays are gone.

That is the change consolidation brings: the journey feels faster because it is faster, even if the single number we track does not show it.

Why It Is Hard to Measure

Part of the difficulty is that the tooling has not caught up. LCP was designed for traditional page loads. It is good at measuring how long the app takes to load the first time, but it cannot yet see the faster transitions inside an app that stays alive as players move around.

There is work under way in browsers to improve this. New standards will allow us to capture those “soft navigations” and report a fresh LCP-like number for each one. But those standards are not widely available yet.

For now we rely on Core Web Vitals because they are the best we have. They give us a consistent way to compare ourselves with competitors, market by market, and to track our own progress over time. That consistency matters, even if it comes with limitations.

Everything in life is a trade-off. Metrics are no different. They are imperfect, but they give us a common language until better tools arrive.

The Broader Lesson

Metrics are still valuable. They let us track, compare and hold ourselves to account. But they are always a proxy. They simplify reality into a single measure, and sometimes that simplification hides the progress that matters most.

Consolidating into a single domain does more than tidy the architecture. It changes the experience for players, and it changes what our tools are capable of measuring. Until standards evolve to capture these in-app movements, we must be careful not to confuse a rising number with a worsening experience.

Because for players, the app feels faster. And that is what counts.