The Integration Dilemma

Balancing integration, adoption, and the lure of best-of-breed.

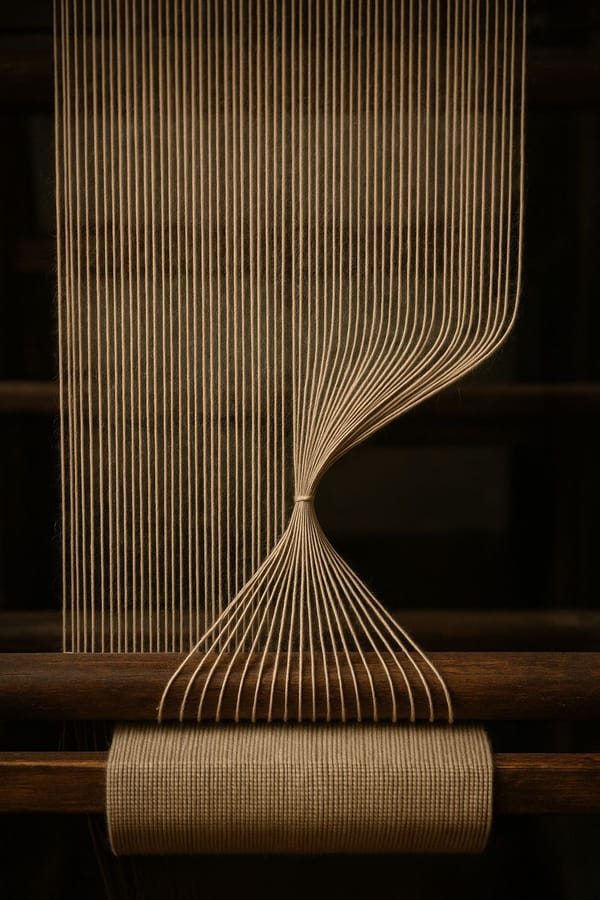

Better a seatbelt worn on every journey than an airbag that sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. A seatbelt is simple, predictable, and compounds its value with every use. An airbag without a seatbelt, and unreliable at that, creates the illusion of safety while delivering little in practice. The same holds for tooling: consistency outperforms brilliance applied sporadically.

That is why many enterprises lean towards integrated platforms that bring multiple capabilities under one roof. They may not be the sharpest tool in every category, but they are coherent, accessible, and predictable. Out of the box, they give teams one login, one workflow, one way of working.

Best-of-breed tooling, by contrast, has an obvious pull. The static code analyser that never misses. The security scanner that claims unbeatable coverage. The analytics suite that promises every conceivable developer metric. Each dazzles on its own.

Yet unless teams deliberately try, the promise rarely lands. Code goes unassessed. Security scanners are never wired into pipelines. Developer metrics never materialise. Procurement is completed, rollout announced, and the harder work never starts. The stitching into a coherent flow is left for later, and later rarely arrives.

Even when integration is attempted, it is fragile. Every connector is meant to smooth flow but becomes a seam. Every seam is meant to hold firm but splits under load. And when seams split, the result is not abstract debt but concrete gaps: bugs that slip through, vulnerabilities that remain unscanned, a lack of insight into velocity.

Sometimes, as in Trading Without a Ticker, the problem is not integration but access. Tools exist, yet the people who need them cannot reach them. Different cause, same effect: insight scattered instead of shared.

The Bombardment of Tools

Product and engineering teams live under a constant barrage of SaaS offerings. Each demo looks like the future: polished interfaces, clever automation, dashboards alive with insight. Many are genuinely brilliant. The harder question is whether they are brilliant enough to justify the cost of integration, rollout, and long-term care.

At small scale, the overhead can be absorbed. At enterprise scale, each new tool ripples into governance, procurement, compliance, and support. Even the most impressive platform can sink beneath the weight of coordination it demands.

Why “Good Enough” Wins

Even if the seams are smoothed, scale brings another challenge: consistency. With thousands of developers, the issue is not whether the tool works but whether it is used in the same way.

Integrated suites bias towards uniformity. One place to commit, one dashboard to check, one release flow. Best-of-breed fragments. One team embraces the full feature set, another barely scratches the surface, a third bends the tool beyond recognition. On paper, the organisation has common capability. In practice, it has a patchwork of local customs.

And even “uniformity” is relative. In a large enterprise, persuading everyone to use the same tool in the first place is hard. Adoption takes leadership, incentives, and persistence. The value comes not from buying the tool but from aligning behaviour around it. Without that, even the most integrated suite will fracture at the edges.

One-size-fits-all also rarely fits perfectly. A standardised tool may feel blunt to specialists or lack the depth needed for a specific context. Yet at scale, the trade-off often favours a common platform. The cost of a few dissatisfied teams is still lower than the cost of endless fragmentation.

This is why “good enough” wins. A tool that meets most needs but is used consistently delivers more value than one that promises perfection but is applied only sometimes. Predictability compounds; capability that is not exercised might as well not exist.

Knowing When Sharpness Matters

Still, there are moments when the sharper edge is the only choice. In a regulated environment, the difference between “almost” and “complete” is not marginal; it is existential. In systems where downtime costs millions, the right analytic view can pay for itself many times over.

Engineers’ appetite for the shiny is not vanity. Curiosity uncovers new approaches. Experiments with the latest SaaS often set the conditions for the next leap forward. Without that instinct, many breakthroughs would never reach production.

The tension will never disappear. Integrated flows give predictability; specialist tools give precision. One compounds value through consistency, the other through edge-case brilliance.

The art is not in rejecting the shiny, but in asking whether the marginal gain in precision outweighs the cost of adoption and integration. Most of the time, it does not. Better a tool that delivers broadly, predictably, and is actually used, than one that dazzles in the corner while the rest of the organisation carries on without it.

In the end, what matters is not the brilliance of the parts, but the fluency of the whole. Just as with safety, it is the seatbelt worn every journey that saves lives, not the airbag that deploys only some of the time.