The Fragility of Both

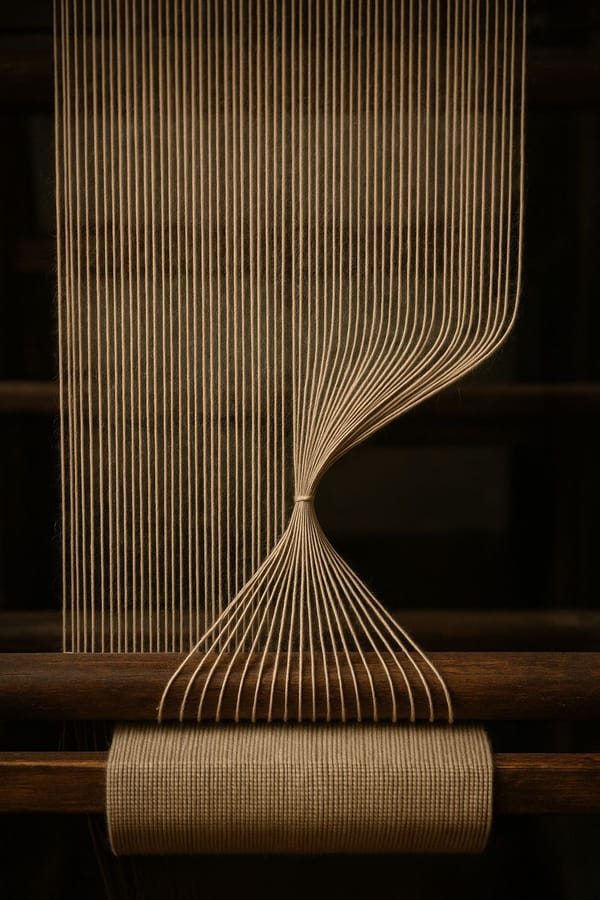

Pipes of different sizes rarely flow well. The trick is to reduce the joins.

Imagine plumbing built over years with pipes of different sizes. Each section works on its own, but once joined together the flow is unpredictable. Sometimes it runs smoothly, other times it slows to a trickle, and nobody is quite sure why. From the outside it looks like one system. Inside it is a set of mismatched parts, connected but never fully aligned.

That is how many mobile apps are built today. A web application lives inside a native wrapper, linked to Android, iOS, a bridge for each, the web layer, and finally the back-end platform. Each layer is solid in isolation, but the joins are fragile. A flow only works when everything lines up, and when it does not, the weak points tend to show through to players.

In a fully native app, drawing on OS features builds on a consistent foundation. The platform and tooling align, and performance is often easier to achieve, though not always a given. That coherence is the strength of native. But when similar features are layered through multiple stacks, the story can become more complicated, as the examples that follow show.

When compromise bites in practice

Authentication is one of the clearest examples, though not the only one.

WebAuthn already provides passkeys, biometrics, and second factors consistently across browsers. It delivers the kind of experience players expect: secure, seamless, device-native sign-in without extra steps.

Yet some implementations still bridge biometrics through wrappers. That leaves authentication spread across Android and iOS, their bridges, the web layer, and the back end. No single tier is fully responsible, so when something behaves unexpectedly, it can take longer to pin down the cause than it should.

Players feel this as unevenness rather than outright failure. Biometrics sometimes succeed, sometimes do not. Sessions may disappear after a background event. These are not dramatic outages, but small inconsistencies that wear away trust over time. For engineers, what might take days to diagnose can take far longer, not because the problem is deeply complex, but because it depends on every layer of the stack aligning at the same time.

Geolocation shows a similar pattern. The web already provides APIs that are accurate and consistent enough for most needs. But once location is split between Android and iOS implementations, translated by two bridges, passed into the web layer, and reconciled with back-end logic, the experience depends on all of those parts staying in step. Even minor drift makes it harder to understand and harder to fix.

Neither case breaks the product outright. Both highlight the same truth: complexity grows fastest where responsibilities overlap, and the experience suffers quietly at the edges.

Where native still earns its keep

That does not mean native has no role. Far from it.

There are times when native gives a product a sense of belonging on the device itself. Think of a balance or score pinned to the home screen, a match that stays live on the lock screen, or a shortcut that takes you straight into the heart of the app. These are the moments players can actually see and feel. They create trust because they look like part of the operating system, not just something running inside it.

Crucially, all of this remains possible even when the core experience is delivered from a wrapper. These features can talk to APIs directly, without being tangled in the bridge, the web layer, or the platform underneath. That separation makes them less fragile, while still giving players the confidence that the app is integrated into their device.

This is the same argument I made in Why Native Still Matters. Native earns its place when it is visible to players, embedded in the OS, and part of their daily rhythm. A coherent web core, complemented by these deliberate native touches, is a path that can feel premium without multiplying complexity.

Chasing improvements players seldom see

It is tempting to believe that native detours create visible improvements. That gestures will be smoother, transitions faster, or sign-in more premium. The reality is usually more modest.

Polish is harder for players to see than it is for teams to build. They rarely notice whether a swipe is processed natively or in the DOM. Modern browsers deliver animations that are already fluid. What they do notice is reliability. They notice when a login behaves inconsistently, or when location permissions feel unpredictable.

So the polish may land occasionally, but the trade-offs are easier to feel. What stands out are delays, inconsistencies, and extra work for teams.

A native detour, not a native progression

Another assumption is that adding more native logic inside wrappers moves a product closer to being fully native. It is unlikely. If a team ever chose to build native end-to-end, the code written inside wrappers would be unlikely to carry across. It is not a foundation to build on. It is a separate path designed for a different architecture.

In practice this means that when native is used where a strong web standard already exists, the maintenance burden grows today without lowering the cost of change tomorrow. The work may be well built, but it does not usually accumulate toward a broader native strategy.

The real choice is between coherence and fragmentation. A web-first approach keeps the stack coherent. Native has its own coherence when used deliberately for OS-level touchpoints. Blending the two rarely brings convergence. It tends instead to create compromise.

Why TWA changes the picture

It is worth acknowledging why the pull toward native is so strong in the first place. On Android especially, WebView has long been a weak link. It is slower, less reliable, and often lags behind the performance players expect from a first-class app. Faced with those gaps, it is natural for teams to reach for native workarounds, and to believe this is the only way to deliver the quality players demand.

The story is shifting. With Trusted Web Activities (TWA), it is now possible to run a Progressive Web App inside a lightweight native shell that uses Chrome rather than WebView. The difference is material. In side-by-side testing, apps delivered through TWA showed a 20 to 25 percent improvement at the 75th percentile compared to WebView. Support for modern standards is consistent, performance is stronger, and the wrapper remains minimal. The result is a web app that feels closer to native without the weight of a full native build.

This matters because it reduces one of the biggest arguments for duplicating native logic. If the pressure to go native was largely driven by WebView’s shortcomings, then TWA softens much of that case. It allows teams to back web standards with more confidence, knowing they will perform well on Android and behave more consistently across devices.

Building with intent

The first step is clarity. If a product is a web app in a wrapper, it should be treated as such. That does not mean lowering the bar. Standards like WebAuthn, geolocation, or CSS transitions are capable of delivering excellent experiences when implemented with care. Clean flows, consistent state, and polished interactions are a product and engineering challenge, not a gap in technology.

For organisations that have already invested heavily in web, starting over natively is always possible, but it is not the only route to premium. With intent, the existing investment can deliver experiences that are polished and consistent without discarding what has been built.

For leaders, the distinction is not purity of stack but quality of outcome. Players value speed, reliability, and consistency more than the label on the technology that delivers it. A wrapper, built with care, can meet that expectation today while still leaving the door open to native if the conditions are right.