The Code Belongs to Everyone

Inner sourcing only works when making changes is easy. Standards make that possible.

Big organisations are good at building walls without intending to. Code splits across multiple repositories, each with its own customs. Pipelines differ, tests run differently, even the folder structure changes. Working across teams becomes less like walking down the corridor and more like having to learn a new alphabet each time.

Why Inner Sourcing Matters

Inner sourcing resists that drift. It treats internal software as open, no matter who “owns” it. A bug seen by one squad can be fixed by another. A shared component can travel more easily. Knowledge and responsibility start to circulate instead of pooling in one place.

For this to work, change has to be simple. Keep the Heart Beating explored why continuity matters in systems. The same principle applies to engineering culture. If the cost of change is high, fixes wait. Lower the barrier, and the organisation heals itself faster.

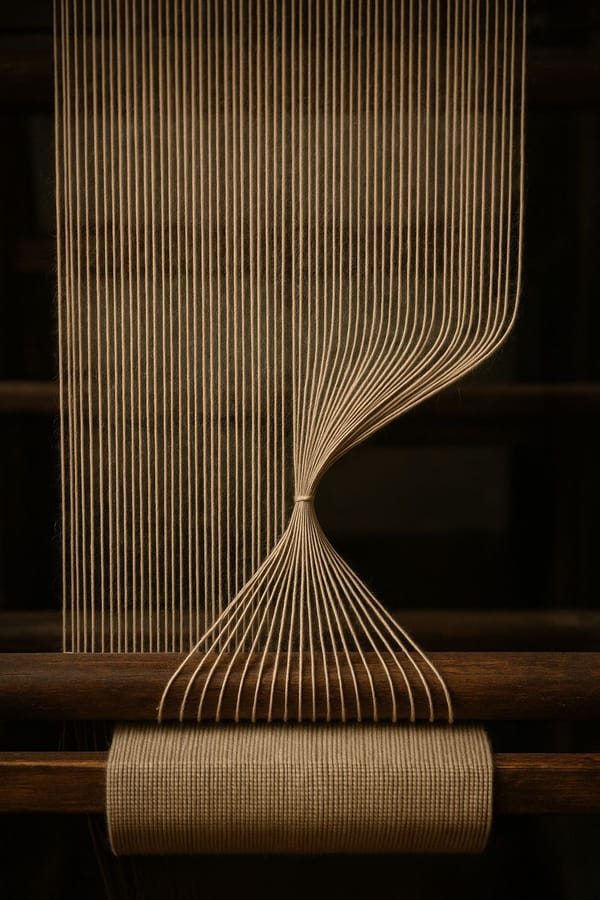

Standards are what make that possible. They are not decoration. They are the phrasebook everyone shares. Once you know how to add a test, run a pipeline, and raise a merge request in one project, the next feels familiar. Engineers can spend their energy on the problem, not on re-learning the grammar of each repo.

Documentation and discoverability matter just as much. If others cannot find the work, they cannot help with it. Contribution guidelines, backlogs, and clear READMEs are the signs that make inner sourcing legible. Without them, an open door can still feel closed. As I argued in Signs Worth Reading, these artefacts are not bureaucracy. They are how intent is made visible, and how teams signal where help is welcome.

Onboarding is another signal. The classic measure of engineering health is whether a new hire is able to make a commit on day one. But why stop there? A stronger test is whether an engineer can make a meaningful change to code for a team they are not part of. If the answer is no, the team might be healthy in isolation but the wider company is not.

Inner sourcing is also part of the antidote to what I described in Lowest Common Denominator Thinking. When every contribution follows the most restrictive path, the organisation slows to match its weakest link. By opening up code and making it easy to contribute safely, we lift the baseline without flattening everything to the lowest standard.

Lowering the Barrier

Permission does not need to be granted in advance. The ability to raise a merge request is itself the invitation. From there it passes through the same protections as any other change: automated tests, continuous integration, and peer review.

That makes participation safer than it might first appear. A merge request is unlikely to break anything. At worst it sparks a conversation, provides food for thought, or becomes the chance to educate. “I saw something I could help with, and here’s my attempt.” That message should be embraced.

A monorepo strengthens that effect. A single place to look, a consistent way to build. Trunk-based development reinforces it by making integration the default. Code moves in small increments to the same mainline, reviewed and tested quickly.

Observability tools such as Datadog are sharper in that context too. When errors can be traced to the exact line of code, it helps if every project lives in the same place and follows the same model. In Refactor, Rewrite, Repeat I pointed to how AI may soon take that further, moving from diagnosis to patch to release. Being ready for inner sourcing extends to AI as well. If we can easily accept human fixes today, we will be better prepared to accept machine-generated ones tomorrow.

The Wider View

For leaders, the value is straightforward. Inner sourcing scales engineering without scaling cost at the same rate. It reduces duplication, spreads knowledge, and makes the organisation less dependent on any single team. The result is resilience: more work moves forward, fewer bottlenecks form, and the company gets a higher return on the talent it already has. It also makes for better engineers. The chance to learn, the satisfaction of progress, and the feeling of trust that comes from freedom are basic human drivers. A culture that supports them will always outperform one that restricts them.

The signs are easy to read. When work is pushed across tickets rather than fixed directly, when new hires take weeks before contributing, or when knowledge is held too tightly by a few, the health of inner sourcing is already in question. The opposite is equally visible. Engineers able to commit on day one, making safe changes beyond their own team, and seeing those contributions welcomed, are all signals of a system that works.

Not everyone finds that shift easy. It can feel safer to stay within familiar boundaries, even if it slows the wider organisation. Yet the real security comes from making it easier for others to contribute, which leads to a stronger product, lower operating costs, and happier players. The effort no longer spent on guarding the walls can be redirected to adding new value elsewhere, the part of the work that players actually notice.

Players never know which team fixed the bug or polished the flow. They only notice that the product works more smoothly. Inner sourcing is one of the quiet ways to make that outcome more likely, turning a workplace of many languages into one where participation is understood everywhere.

So it is worth asking: why should something so common in open source feel like an imposition within corporate walls?