Shaping Architecture Through Behaviour

The chart is not the system. The system is what teams make visible.

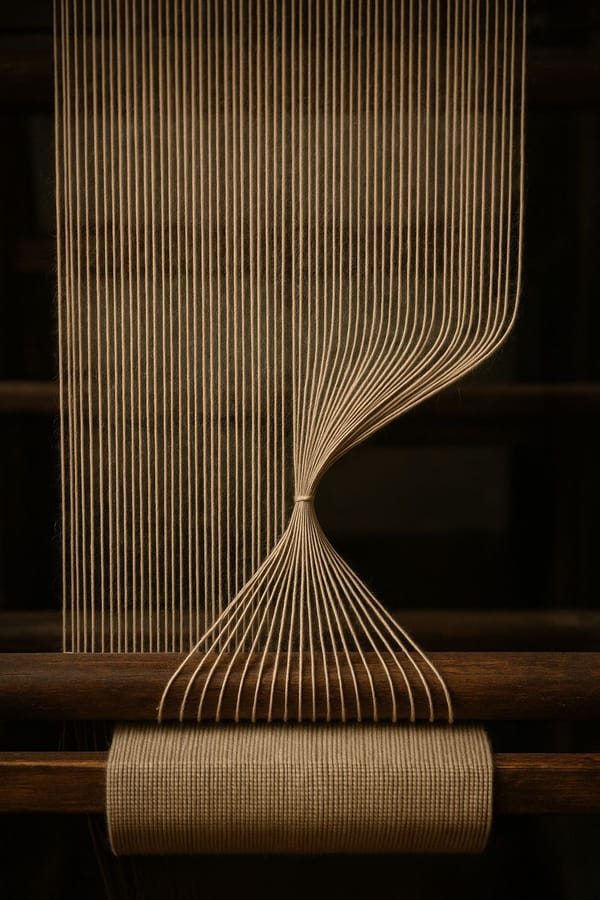

A flock of birds has no master plan. Each bird follows a few simple rules – keep close, do not collide, match direction – and the result is a pattern that looks choreographed. Try to draw the outline and it will already have changed. Enterprise architecture often tries to do just that: capture a living system on paper. The picture slips out of date almost as soon as it is made.

The intent is usually sound: leaders want visibility and teams want clarity. Yet silos appear all the same.

The challenge is that if documentation is stale, dashboards are ignored, or incident tickets are vague, the chart becomes theatre. It reflects not the health of systems but the absence of the behaviours that would make them visible.

First the habits, then the tools

That is why starting an EA function with tool selection is risky. A platform promises order, an inventory promises insight. But choosing a tool is rarely the best first move. It may come later, once behaviours are established, or it may follow naturally from the standards already in place. Without those foundations, the tool is decoration.

The stronger starting point is to decide what behaviours matter. How is work described? How are systems documented? How are incidents recorded and metrics trusted? With those practices in place, almost any EA tool will do. Without them, no tool is enough.

A catalogue of good intentions

The gaps become clearest when things fail. Bugs may appear in an incident service, in a backlog, or in monitoring data. Some link to code changes, many do not. Others live only in chat threads or calls that leave no record. The story of what happened is fragmented.

The question is whether EA can ever surface that mess. In an organisation with thousands of engineers and services, the fragments are too numerous and too fluid. Even if collected, they are too far from the work to act upon. At best, EA produces a catalogue of issues. At worst, it presents a tidy picture while the reality remains unresolved.

Services are renamed, pipelines fork, flows change hands, but the inventory remains static. By the time a review comes around, the neat list no longer matches what anyone is running.

From time to time organisations attempt to baseline the entire architecture. On paper this has value: a fresh view can cut through local detail and give a shared frame of reference. The harder truth is that the odds are against it. In complex organisations signals are inconsistent, flows change quickly, and inventories drift before the ink is dry. It is not impossible – with intent and discipline it can work – but the larger the scale, the faster the picture slips out of sync.

This is more than a tooling gap. It is a continuity problem, the same theme explored in Keep the Heart Beating. Without reliable behaviours, the system cannot heal itself, and signals are lost just when they matter most.

Illusionary control

The consequences are tangible. Teams launch products without load tests. Services collapse under traffic, leaving central infrastructure groups scrambling to provision capacity. EA may respond with more approvals and review boards, but it can slow delivery while obscuring accountability.

A more effective response is to move responsibility closer to the work. Site Reliability Engineers embedded within product squads change the incentives. When the same team that builds a service is accountable for its resilience, shortcuts are felt immediately. Combine that with platform engineering – paved roads for deployments, observability, scaling – and you get both autonomy and guardrails.

This does not mean architecture has no place. ADRs and technology advisory forums remain important, particularly where decisions cut across teams. Shared components, data platforms, and security standards demand coordination. Not everything can be “you build it, you run it.” The role of forums is to enable decisions, not replace them. They should lift the floor without pressing down the ceiling.

The greater risk is control that exists only on paper. EA can present coherence while the underlying systems drift.

When product meets architecture

The product operating model puts accountability with teams. They own outcomes, they own technology choices, they move at the speed the market demands. Traditional enterprise architecture pulls in the other direction, promising coherence through standards, catalogues, and central oversight. At first glance, the two are in conflict.

A modern EA function looks different. Its role is less about drawing diagrams and more about creating conditions for product teams to succeed without losing coherence. That means:

- Platforms as the enterprise layer. Shared infrastructure, deployment systems, and observability form the common ground. Teams can move quickly, but they do so on a surface that is already hardened and cost-aware. This is the paved-road approach I have written about elsewhere: opinionated paths that still allow flexibility.

- Advisory forums, not approval boards. Architecture discussions happen across teams, not above them. Decisions are still debated, but the aim is enablement, not gatekeeping. This is where the spirit of Refactor, Rewrite, Repeat applies: align on when change is worth the cost, and when to stay the course.

- Principals, not distant architects. Architectural accountability sits inside domains. Principal engineers design and deliver in the same breath, carrying the trade-offs in their own systems. This echoes The Trunk is the Team: coherence comes from people and code evolving together.

In this form, EA is not in conflict with the product model. It becomes the counterpart that makes it sustainable at scale. The tension does not disappear, but it becomes productive. Autonomy is preserved, coherence is maintained, and neither side has to pretend the other does not matter.

Architecture as an outcome

Perhaps the sharpest way to think about EA is not as a function at all, but as an outcome. The catalogue, the visibility, the flow of decisions across teams – these are what emerge when product engineering is healthy. When documentation is alive, dashboards are trusted, and incidents are linked, you already have architecture. It is visible without needing a separate group to describe it.

None of this is to dismiss enterprise architecture itself. The aspiration to see the whole, to make sense of complexity, is a worthy one. The intent is good, but it is so hard to keep true that it rarely succeeds in practice.

Fixing behaviours so they match the practices described in this blog is not simple either. It is one of the hardest jobs in engineering leadership. The difference is that it creates sustainable value. When teams write clear tickets, keep documentation alive, and trust their dashboards, the system changes. The product operating model reinforces this by placing accountability with the teams themselves. EA can show the picture, but without those behaviours the picture does not alter the reality.

Where it fits, where it doesn’t

Enterprise architecture does find steadier ground in more traditional IT domains. Areas such as infrastructure, office systems, and enterprise applications change at a slower pace. Standardisation here brings clear benefits: fewer platforms, simpler support, and lower cost. Catalogues can be kept current, and central oversight can add real value.

In product engineering the fit is weaker. Releases are frequent, autonomy is essential, and dependencies shift quickly. Here coherence emerges through behaviours, not through central diagrams. The same mechanisms that make EA useful in traditional IT – catalogues, baselines, inventories – struggle to keep pace in a product model.

Holding the balance

As I wrote in Shouting in the Digital Office, you know you are doing it right when you do not need to communicate explicitly. A healthy system does not need a chart to declare it green, or a committee to certify compliance. Its health is already visible in how it runs: in the reliability of deployments, the trustworthiness of dashboards, the clarity of commits and tickets.

The role of leadership is to hold that balance. The intent to improve must not slide into control without substance. The desire for visibility must not become theatre. Enterprise architecture will almost certainly exist in some form. The question is not whether, but what shape it takes. The healthier shape is not a tower of charts, but an enabler of behaviours.