Not Just Upwards

A healthy system creates space to rise, and has the strength to let go.

Promotions draw the spotlight: simple to announce, easy to celebrate, designed to be visible. Without performance management, though, a company can drift into becoming a de facto pyramid scheme. No one designs it that way, but the effect can be much the same.

Succession is often framed in terms of who is ready to step up, who is being prepared for more. But succession only works if the whole system is healthy. If attention falls mainly on those moving up, the organisation risks losing strength elsewhere.

Many organisations frame performance management as an HR process. Reviews, calibrations, ratings. These provide fairness and consistency, and they are essential. But HR alone rarely catches the real signals. They sit too far from the day-to-day work. Only in partnership with leadership can those signals be surfaced and acted on. Neither side is able to do it on their own.

Latency in the system

Underperformance often behaves like latency in a system. Ten milliseconds here, another fifty there, each delay seems tolerable, but together they accumulate into something players notice.

In engineering, the response is to look for the bottleneck, refactor the code, or adjust the design. Underperformance deserves the same treatment. Not punitive, but systemic.

The engineering examples are familiar. Builds that fail again and again. Defects that resurface release after release. Branches destabilised by merges. Environments that take too long to provision, slowing every attempt to test and ship.

Left unresolved, these bottlenecks shape the whole system’s pace. And just as systems suffer from repeated drag, so too can people. That is where the signals shift from technical to human.

Signals in the noise

If technical latency slows a system, the human signals show up in how people work together. They are rarely dramatic, more often small behaviours that wear on momentum. Work that changes hands too many times before it is finished. Meetings that stretch on without producing a decision. Effort poured into tasks that stall before they are usable. Ownership that drifts rather than being taken.

On their own, these moments may seem minor. Taken together, they shape the rhythm of a group. Patterns emerge: reluctance to step outside a narrow role, defending process instead of progress, raising problems without bringing enough clarity for others to help.

These rarely surface in quarterly reviews. They are felt in the daily flow, in the way one person’s habits affect many.

The price of progress

Failure itself is not the problem. Trying and failing is often the price of progress. Features that miss, prototypes that break, experiments that do not hold up. These are how teams learn and how products improve.

Underperformance is something else. It is not the one-off failure that teaches, but the repeated behaviour that drags. It is not an experiment that did not work, but the unwillingness to adapt after it did not. Progress is built on the first. The second quietly erodes it.

The work of lifting people

Leadership is not only about removing obstacles for the team. It is about lifting people up, one by one. Coaching, direct feedback, and deliberate development are the first steps when performance falters. Many engineers do not lack ability. What they need is context, guidance, or the confidence that comes from being trusted with more.

The role of a leader is to make those opportunities visible and to support improvement when it is possible. That is part of developing people, and it is as important as designing systems or delivering features.

That support often works, and when it does not, it is not necessarily a failure. There comes a point where coaching has been tried, where feedback has been clear, and where the pattern does not change. At that point the responsibility shifts. Sometimes that means recognising it is time to part ways. Continuing to avoid the decision does not develop the individual, and it harms those around them.

The drag of avoidance

Avoiding a performance conversation with one person may feel like kindness. But avoidance often creates a quiet unfairness. The strongest performers absorb the extra load, the team’s confidence thins, and the individual at the centre is left in uncertainty.

Slippage often starts here. An engineer may be capable in their domain but refuse to work outside it. Every cross-cutting change falls to someone else. Meetings stall because more time goes into defending process than addressing problems. Colleagues shoulder the work for a while, but patience wears down. Without a reset, everyone remains in limbo.

The reverse is also true. Some individuals face the same friction but respond to clear expectations. Once the standard is visible, behaviour can shift quickly. What was a source of frustration becomes manageable, and the group regains rhythm.

At scale, inconsistency becomes its own form of unfairness. If some leaders avoid the hard calls while others do not, the organisation teaches two different lessons at once.

Direct conversations make the standards visible. They give someone the chance to adjust. If adjustment is not possible, they make the outcome clear. Avoidance does neither.

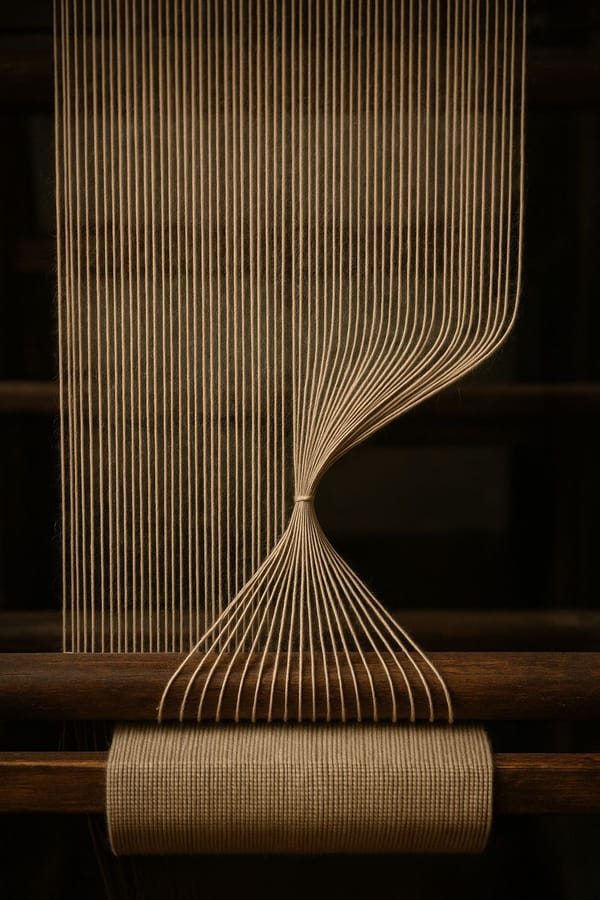

Flow to the player

For a product engineering organisation, this is not a side concern. It sits in the same category as architecture, developer tooling, and product direction. Each affects flow, and each ultimately reaches the player.

When underperformance is ignored, output slows, trust weakens, planning becomes unreliable, and momentum itself can grow fragile. What begins with an individual spreads into the team. Handled well, the opposite happens: standards are clearer, weight is shared more fairly, and products arrive with fewer surprises.

Scaling performance management is less about adding process and more about rhythm. When expectations and conversations happen predictably, they stop being exceptions and become part of how the organisation works. That consistency is more than a cultural good, it is often a competitive advantage.

The point is not comfort. Done well, performance management creates momentum for the organisation and the players. Momentum can come from a promotion, a change in behaviour, or an exit.