Lowest Common Denominator Thinking

Choice beats compromise.

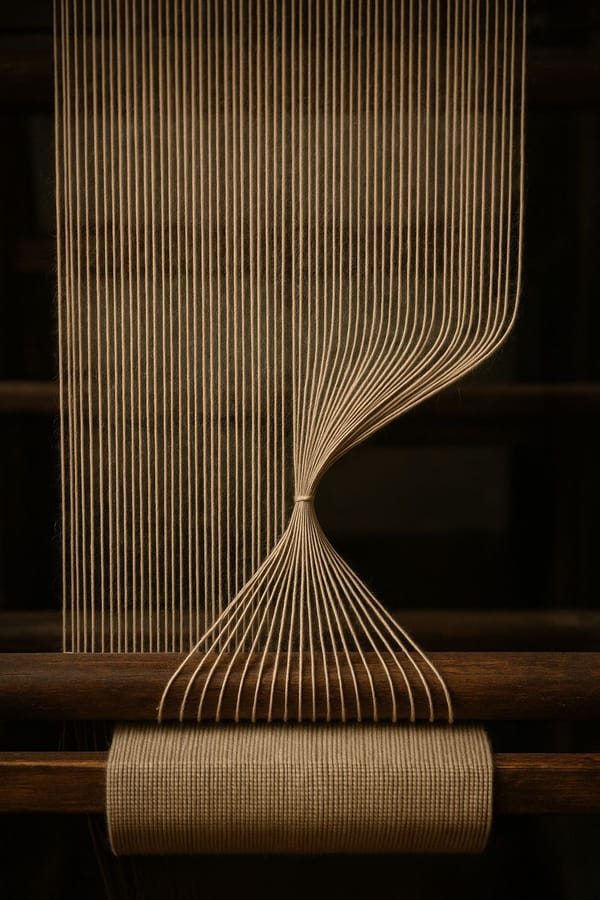

Imagine a dish cooked for a long table of diners. One cannot tolerate heat, so the spice is left out. Another avoids salt, so the seasoning is dropped. By the time it is served, everyone has something on their plate. For the few with strict diets, it works. For the many, it is less satisfying.

That is lowest common denominator thinking. You design for the most restrictive case, and everyone else pays the price.

For global companies this is not a theoretical risk but a daily trade-off. Expanding into new markets demands both speed and local nuance, while internal processes must balance safety with agility. Without strong product engineering foundations, the choice often collapses into two extremes: flattening everything into something consistent but less distinctive, or forking repeatedly and carrying the long-term cost of divergence. Both are understandable, but both are limiting. They appear in two places: in how products scale across markets, and in how internal processes slow delivery to the pace of the weakest part. Product engineering is the mechanism that turns leadership intent into outcomes.

Markets Made Safe

Global products often lean toward the lowest denominator to make scale possible. Local quirks are set aside, campaigns adjusted, and pricing simplified into a single model. This can be efficient, but it risks reducing distinctiveness and sometimes mismatching local conditions.

Digital experiences follow the same line. By designing for the poorest connections, players on fibre and 5G are never offered the richer experiences their networks could support. The outcome is usually safe and consistent, but rarely as engaging as it could be.

This is not the result of weak ambition. More often it reflects the constraints of the underlying foundations. When the technology cannot support variation at scale, leaders sensibly choose simplicity. What looks like a brand decision is often a product engineering decision in disguise.

Engineering That Enables Localisation at Scale

When products expand across many markets, the choices often fall along a spectrum. Flattening creates consistency but reduces local resonance. Forking gives autonomy but risks duplication and divergence. Both can make sense in context.

Selective forking, in some cases, may be the least damaging option. A market might need its own frontend or integration to meet local conditions, and in those moments forking can be the pragmatic choice. The challenge is that forks carry costs: duplication, divergence, and added maintenance. Whether they remain exceptions or become permanent fixtures depends on how the organisation chooses to manage them.

Modern product engineering makes it possible to stay in the healthier middle ground, where local teams can innovate without losing coherence. Feature flags and experimentation prove what works before scaling. Modular architecture, design systems and well-governed APIs create a consistent base with space for variation. A monorepo and inner sourcing allow local teams to contribute directly to the shared platform, strengthening the whole while retaining local capabilities. Shared telemetry, automation and observability provide stability at speed. Platform teams enable rather than block. And underpinning it all is the courage to retire brittle systems, so the new practices do not sit on top of old fragility.

Handled this way, localisation does not force flattening or unchecked forking. It allows variety without chaos, distinctiveness without sprawl. The commercial pay-off is clear: faster entry to new markets, higher likelihood that local patterns convert, fewer outages and lower operating costs over time. With the right foundations, product engineering becomes the enabler of localisation at scale.

Internal Processes That Slow Us

The same pattern appears in processes and workflows. Rules written for rare exceptions end up applied to everyone: a brittle service halts releases across the estate, a sign-off designed to avoid risk stretches review cycles into weeks, compliance forms multiply risks that will never apply. Tooling can make it worse, with each team insisting on its own flavour of platform until the organisation bends under the friction of sprawl. Talented engineers are slowed to the pace of the least capable workflow. What begins as a desire for fairness or flexibility ends up as inertia.

The way forward is not carelessness but discipline. Trunk-based development keeps code moving without endless merge bottlenecks. Automated pipelines replace manual gates with fast, reliable checks. Observability makes it possible to fix issues quickly rather than slowing everyone to prevent them in advance. Practices like these shorten lead times, stabilise quality and reduce rework. That compounds into faster time to market, better customer experience and leaner operating costs, while keeping the safety bar intact.

Respect Without Uniformity

Whether in product markets or internal processes, lowest common denominator thinking often disguises itself as compromise. It looks like balance. It looks like fairness. But compromise can leave everyone worse off. Chris Voss once pointed out the flaw: if one traveller wants Paris and another Rome, splitting the difference lands you in Geneva airport, a place nobody asked for.

There are moments when the denominator must set the pace. Accessibility, inclusivity, safety, regulatory compliance. In those cases, serving the few serves us all.

Many other times the real driver is inertia. Fragile systems are preserved not out of respect but out of fear, and processes end up slowed as a result. True respect is not giving everyone their own way. It is giving each what they are capable of, within a clear frame. That means differential builds rather than infinite variation, common platforms with space for local nuance, and teams trusted to move at their natural pace while staying aligned on standards and direction. Good governance sets the floor. Good product engineering sets the pace.

Choosing the Denominator

Leadership is about deciding where to place the denominator on the spectrum. At one end sits complete flattening, where everything looks the same and local resonance is reduced. At the other sits unchecked forking, where every market goes its own way and the organisation carries the cost. Somewhere in between lies the balance: a shared base with room for variation, enabled by modern product engineering and strengthened by contributions from local teams.

The same choice plays out in processes. Rules can be written to protect against the rarest failure, but if applied to everyone they slow the entire company to its weakest point. The art of leadership is recognising when protection is essential, such as safety and regulation, and when it is inertia in disguise.

The lowest common denominator is tempting because it feels safe. Nobody is excluded, nobody is criticised. Yet it leaves you with meals that are filling but unremarkable, products that are consistent but less distinctive, and processes that teams stop believing can change. The meals that linger in memory are the ones with flavour, shaped to each individual yet shared at the same table.

The real opportunity is optionality. Invest in product engineering and you expand the menu of choices. Local teams can innovate while still strengthening the platform. Forks can be used when needed, but deliberately and with awareness of their cost. And leadership can choose the denominator with confidence, knowing the organisation has the flexibility to adapt, the distinctiveness to stand out, and the efficiency to keep operating costs under control.