Keep the Heart Beating

The case for a common process supervisor.

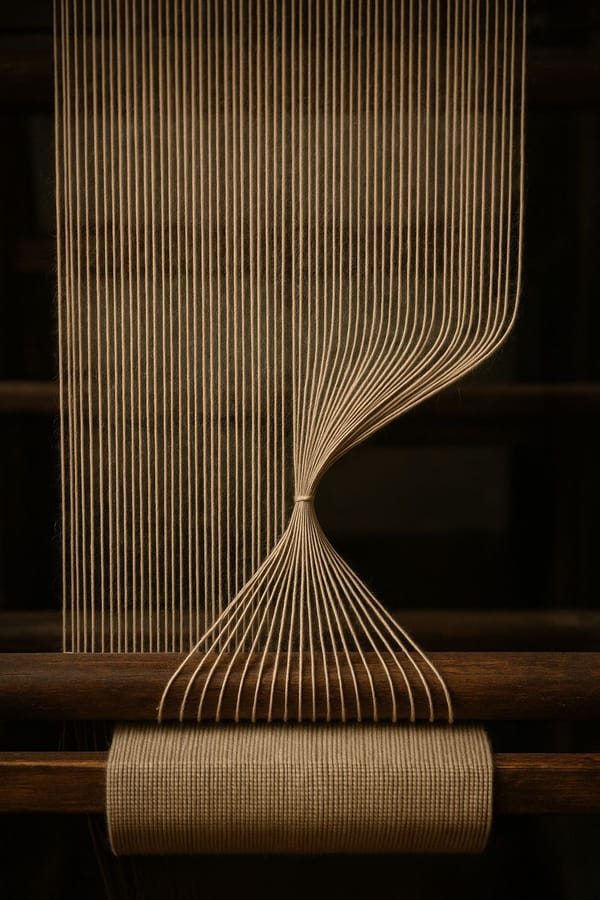

Running services without a supervisor is like fitting a pacemaker that only records when the heart misses a beat. The data would be accurate, but the patient would not survive long enough for it to matter. A real pacemaker intervenes first. It keeps the heart beating, and then leaves a record of what went wrong. Services deserve the same treatment.

Failure is not optional

Services fail. That is a constant. What varies is how organisations respond. Some notice quickly, some only after colleagues complain, and some rely on someone in operations to restart things by hand.

Engineers sometimes resist automatic restarts. The concern is that if a service comes back by itself, the signal of failure will be hidden. The instinct is understandable: it comes from a desire to know what went wrong. But leaving a service down so that failure is obvious is the wrong trade-off. It makes everyone who relies on the system pay the price so that engineers can notice.

Continuity and observability are not in conflict. A process supervisor can restart a service automatically and at the same time record the fact that it failed, how often, and why. Colleagues are not blocked, and engineers still see the signals they need to act on.

Too many cooks, too much config

Init scripts were brittle and often hand-written. Supervisord came next, then systemd, each adding more capability and more complexity. Kubernetes goes further still with liveness and readiness probes.

These systems have their place, but they also add overhead. Init scripts are fragile. Systemd can be sprawling and opaque. Kubernetes solves orchestration, not day-to-day process reliability in a VM estate. For organisations running large fleets of services on traditional infrastructure, the result can be fragility disguised as sophistication.

Tech debt in disguise

Stacks often come with their own supervision features. The JVM has wrappers. Python servers like Gunicorn can respawn workers. Node has forever and nodemon. Each works locally, but across an organisation they introduce inconsistency. Operations staff must learn a different model for each stack. Support needs different runbooks. Reliability becomes uneven, depending on which team bolted on which layer.

Language-specific supervisors solve one team’s problem while creating debt for everyone else. They embed process management into application code instead of treating it as a shared capability. The result is operational drag: more surface area, less consistency, and reduced trust.

When the supervisor falls asleep

Even purpose-built supervisors stumble. A systemd unit may sit in a “failed” state without being restarted. A language wrapper may quietly give up. The effect is the same: the process is down, but the supervisor believes it is up.

Daemontools has avoided this trap. Its design is small and strict, which keeps it aligned with reality. If a process dies, it is restarted. If it is marked down, it stays down. If it is running, it is running. In production use across many environments, it has proven consistently reliable.

Boring, on purpose

Daemontools is mature, stable, and simple. Each service lives in a directory with a run script. That script makes intent explicit. Should the process restart automatically? Should it come up on boot? Should it stay down until called for? These decisions are clear and visible.

It speaks every language

Daemontools does not care what the process is. Java, Clojure, Python, Go, or anything else: if it can be started with a command, it can be supervised. This neutrality allows a single approach across the stack. Starting and stopping services follows the same pattern across environments. In a heterogeneous estate, that consistency matters. It means SREs and support staff can intervene with confidence, without needing tribal knowledge or waking a developer at three in the morning.

Rollbacks out of the box

The model also makes deployments straightforward. Multiple versions can sit side by side: myapp-v1.2.3, myapp-v1.2.4. The one that runs is whichever the symlink in /service points at. Promoting a release is repointing the symlink. Rolling back is the same. It is atomic, transparent, and reversible.

There is no separate deploy system, no hidden metadata. The filesystem itself is the source of truth. Anyone can see which version is live, which versions are available, and how to switch.

Observability is part of the design. Logs show whether a process is restarting repeatedly or sporadically, always in the same format. The behaviour is predictable. The same commands apply across services.

Respect the people, not just the processes

The outcome is human, not abstract. Administrators make fewer mistakes. Developers spend less time chasing failures. People who rely on the systems experience fewer outages and less disruption.

And this is the point that matters most. Product engineering depends on these processes being up. When they are not, features stall, releases slip, and colleagues lose confidence. As an organisation we owe it to each other to remove that risk. A common process supervisor is not just a technical convenience. It is a way of showing respect for time, trust, and focus.

Choosing not to use one is not neutral. It adds toil and risk. It undermines stability. Daemontools shows that a simple tool, applied consistently, can provide stability that is otherwise hard to reach. Reliable processes are not only good engineering; they are a responsibility we hold to the people around us.