Federated Design Systems: Global, Brand, Product

One wardrobe, many uniforms, one team.

In a multinational the real challenge is scale. Dozens of brands, each with its own history. Products that range from simple to sprawling. Markets that stretch from são paulo to sydney. Without a design system, the result is a patchwork of interfaces that are inconsistent, follow varying standards, and repeat the same work in different places.

What a Design System Is and Isn’t

A design system is a shared library of tokens and components. Tokens are variables such as colour, spacing, type scale, and motion curves. Components are assembled parts such as buttons, inputs, cards, and menus. Together they form the grammar of the product and give teams a common baseline.

It is not a shortcut to finished products. You cannot use a design system to spin up new journeys or business logic. Those still need to be designed, coded, and tested. The system provides the building blocks, not the blueprint. Its purpose is to strip away duplication so teams can focus on the work that is genuinely new.

Federation in Practice

Global, brand, and product teams face different pressures. Global wants consistency and quality. Brand wants cultural fit and voice. Product wants speed and room to adapt. A single global system tilts too far one way. Letting every team improvise tilts too far the other.

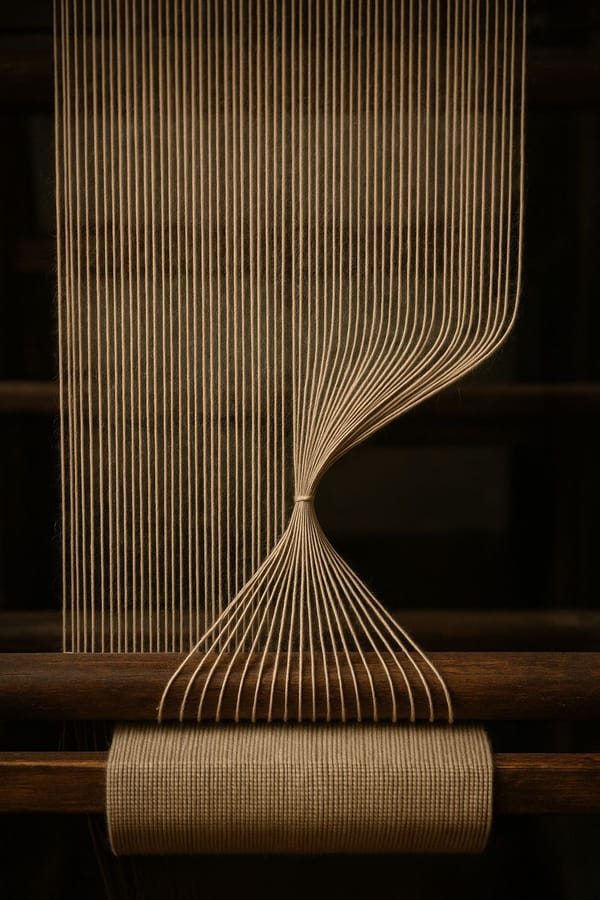

Federation balances the tension. It creates a hierarchy of layers where each level imports and extends the one above it.

Storybook is the tool that makes this visible. It is an environment where designers and engineers can build, browse, and test components in isolation. Each button, card, or form can be shown with its different states and variations. When federated, storybook becomes more than a gallery. It becomes a map of the system across global, brand, and product layers.

At the global level, rules are strict. Accessibility, spacing, and motion are non negotiable:

<button variant="primary">submit</button>

// global baseline: enforces accessibility and spacing

A brand layer inherits this baseline but applies its own palette and typography. The markup looks identical, but tokens differ depending on which brand is consuming it:

<button variant="primary">submit</button>

// brand layer: same markup, styling context changes by brand

A product layer builds on top to meet domain needs. In a sportsbook the value is the odds themselves:

<button variant="odds">2.5</button>

// product specific: tailored for displaying betting odds

In a casino, the priority is action rather than numbers:

<button variant="spin">spin</button>

// product specific: adapted for casino interactions

Each layer looks simple in isolation, but the hierarchy matters. Global enforces non negotiables. Brand adapts for cultural voice. Product shapes behaviour for specific journeys. Together they keep the system coherent while still leaving room for difference.

Contribution and the Triad

Federation only works if it flows both ways. Local invention must have a path back up. A new component for right to left text may start in one product. If it proves valuable, it can move into the brand layer. If it has global application, it can be standardised at the top.

That contribution model relies on a triad of disciplines working together. Design brings the eye for accessibility, coherence, and visual language, making sure new components do not break the grammar of the system. Product brings the player view, asking whether a change addresses a real need and fits into the broader journey. Engineering brings the technical lens, checking that the component performs well, can be tested, and will hold up at scale.

No single discipline can carry a change on its own. When the triad works in balance, improvements spread quickly and responsibly. How to govern this in practice is still an open question. Should global teams act as curators, should brands have councils, or should the system behave like open source with maintainers and reviews? The answer matters less than making sure the path upward exists.

Already Standard Practice

Most large organisations already compose global tokens, brand overrides, and product specific variations, even if they do not label it federation. Storybook and figma support composition. In a monorepo this becomes straightforward, because every team works from the same source of truth and has a clear place to contribute.

The real choice is whether to federate deliberately. Forking design systems looks like autonomy in the short term but leads to divergence and decay. Federation is the path to scale without collapse.

Reaching the Tipping Point

In many large organisations a design system is not introduced on a blank canvas but retrofitted into products that already exist. That makes scepticism inevitable. A colour palette in figma or a shared css file is not a design system, and calling it one too early undermines trust.

The tipping point comes when tokens are centralised, components exist in code, and adoption reaches a critical mass. A system can be said to exist the day new work defaults to it.

The early phase often feels like overhead, another library to maintain. The proof arrives when a team delivers faster by reusing rather than rebuilding. From that point the pattern spreads. Products begin to adopt the system, and new features are built from its components where they exist. Legacy journeys take longer to retrofit, but forward momentum becomes clear.

Once that momentum is established, rules can be introduced to stop teams from bypassing the system. Linting checks, review gates, and design sign off make sure new components are added to the system rather than created in isolation. The shift is important: what began as guidance becomes the default path, and the exceptions need justification.

Why It Matters for Players

The impact is visible at the edge. Players move between products and even brands without being jarred by sudden changes in behaviour. Improvements made in one market spread quickly to others. Journeys break less often because fixes ripple through the hierarchy instead of being patched separately in each fork. Consistency is not about making everything look the same. It is about making the experience predictable and trustworthy while still allowing each brand to feel distinct and relevant in its own market.

Beyond the Lowest Common Denominator

A federated design system provides structure without stifling. Global safeguards quality. Brand asserts identity. Product adapts to journeys. Each layer has clear responsibility and a way to influence the others.

The deeper value is cultural. Teams stop asking “what is the one safe option we can all agree on” and start asking “what can we contribute that others might use.” Improvements flow upward. Standards flow downward. The system becomes a living mesh rather than a frozen rulebook.

This is the opposite of lowest common denominator thinking. Instead of trimming difference until nothing remains, federation encodes difference into the architecture. The result is coherence. Products are consistent enough to be trusted, but distinct enough that each brand still feels like itself.