Beyond Squads: The Case for Centres of Excellence

When muscles and nerves aren’t enough to stand.

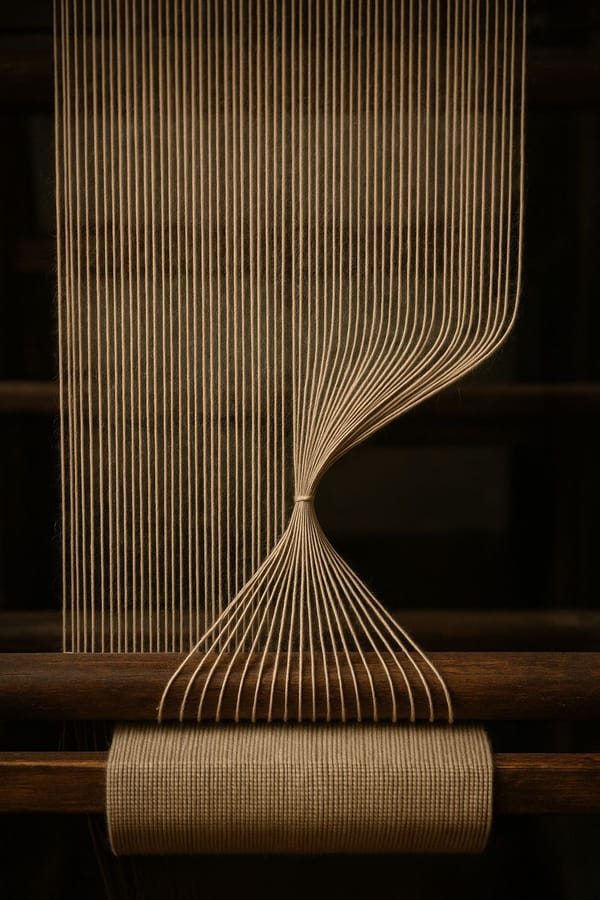

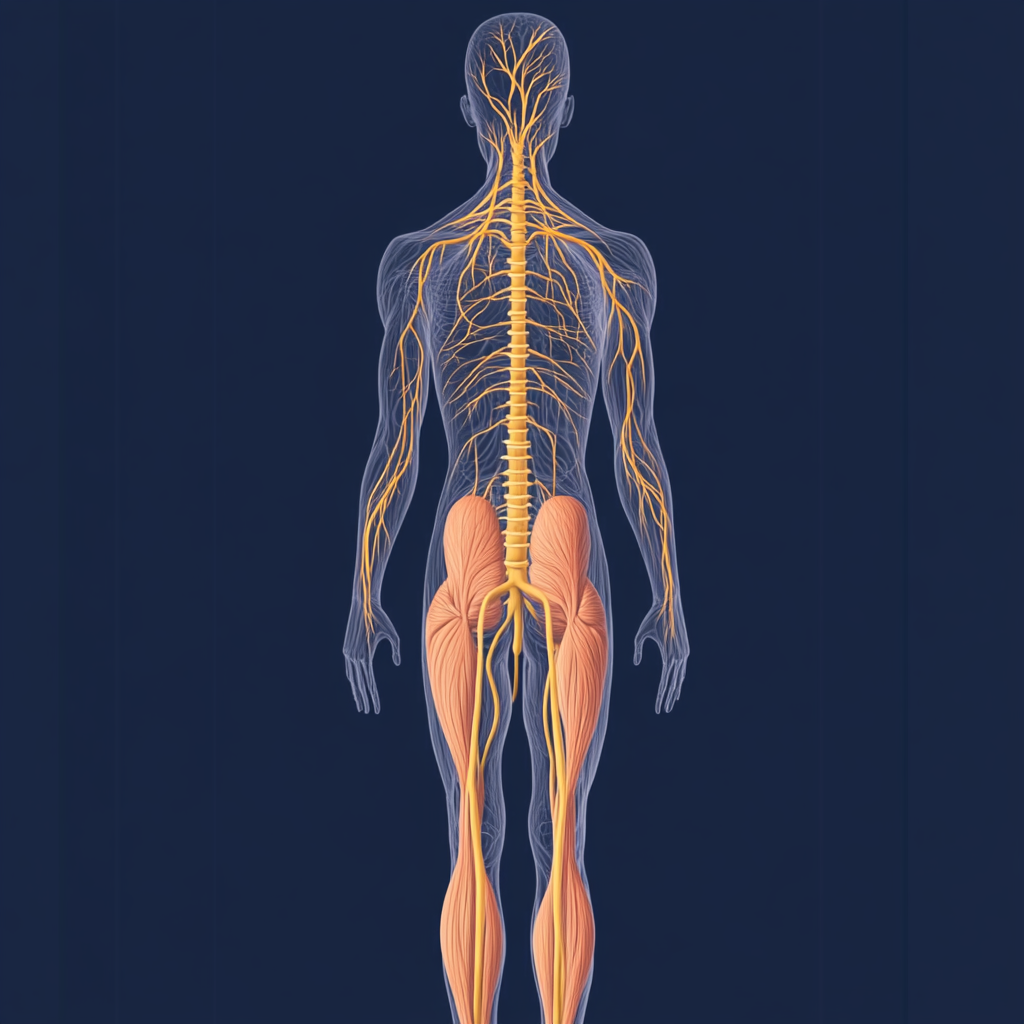

Every muscle in the body can contract on its own. Squads are the muscles of an organisation, powering features and outcomes. Guilds are the nervous system, transmitting signals, sharpening reflexes, and helping the body learn. But muscles and nerves alone cannot hold a body together. Without a spine to support and coordinate them, the movement collapses. Centres of Excellence can be that spine, providing the strength and stability that autonomy alone cannot.

Squads and Autonomy

The product operating model puts squads at the centre. They are cross functional, durable, and autonomous. They own outcomes, not outputs. You build it, you run it, you own it is a corrective to the bottlenecks and handoffs of project delivery.

But muscles can only contract. They need support to coordinate. Left alone, they twitch in isolation. Autonomy without connection is incomplete.

Guilds and Knowledge Sharing

Guilds are the nervous system. They pass signals across the organisation. A testing guild swaps patterns for stabilising pipelines. A design guild shares tokens and typography. A developer experience guild refines tooling and process.

Inner sourcing extends this idea. Frameworks and libraries opened to contribution allow squads to improve shared assets as if they were open source. A bug fixed in one context becomes a benefit for all. This works well for incremental improvements and small fixes.

Signals and contributions matter. But nerves alone cannot hold weight. A guild can spread awareness and an inner source model can capture contributions, yet neither will consistently solve the deepest problems. Knowledge moves, but energy does not.

When Centres of Excellence Need to Do the Work

Centres of Excellence are often described as enablers, creating dashboards, libraries, and paved paths so squads can move faster. That helps, but systemic problems rarely move through enablement alone. Some issues demand ownership and direct intervention.

Performance is the clearest case. A memory leak is not a one-off bug. It takes deep expertise to profile the heap, trace the leak, and prove the fix. Even then, the answer is often not a patch but a new pattern that requires refactoring code across the entire base. No single squad will take on that work. It is too large, too invisible to players in the short term, and too easy to defer in favour of features that promise more immediate business value.

Inner sourcing can help with smaller contributions. A squad that optimises a flow or patches a dependency can share that fix and spread improvement. These contributions are valuable.

But systemic performance issues are different. They demand sustained focus, broad coordination, and expertise that does not exist in every squad. They require not just a fix, but the discipline to apply it across every code path, every product, and every brand. They often require research too: benchmarking, profiling at scale, and experimentation with patterns that may disrupt existing code. Action matters, but without investigation the wrong fixes spread quickly. Squads under pressure to ship features rarely have the mandate for this depth of work.

In theory every squad could do this work. In practice it rarely happens at scale. Players do not see the benefit immediately, business priorities push features to the front, and developers feel the weight of complexity without the air cover to act. Teams do improve over time, and some do take on systemic problems when conditions allow. But the pace is uneven, and the gaps left in the meantime can accumulate into serious issues. Centres of Excellence exist to carry the deep, wide work that cannot wait for every squad to reach maturity.

Why Organisations Resist

Organisations often resist Centres of Excellence. Sometimes it is cost: why fund a team when squads could, in theory, solve their own problems? Sometimes it is fear: many remember central teams that turned into gatekeepers. And sometimes it is optimism: given enough cycles, squads do improve.

These concerns are valid. Cost matters. Gatekeeping must be avoided. Squads do improve when given space. But can you afford to wait? In a large organisation, drift compounds. Every month without a spine is a month where performance slips, pipelines clog, and compliance weakens. Certainty today often matters more than waiting for every squad to reach maturity tomorrow.

Avoiding Learned Helplessness

If Centres of Excellence do too much of the work, squads may start to abdicate. Why debug the memory leak if the performance team will eventually fix it? That way lies centralisation in disguise, where responsibility drifts upward and autonomy becomes hollow.

The answer is not to retreat from CoEs, but to design them carefully. They should tackle the hardest systemic work while still ensuring squads remain accountable for their outcomes.

Three practices make this balance possible. Engineers should rotate between squads and CoEs so knowledge flows both ways. Responsibility should always return to squads once the fix is made. And adoption should be the measure of success. A tool or library unused is wasted effort. A process that spreads across squads is impact.

Some squads will still neglect performance or testing, hoping a core team will step in. When that behaviour repeats, it is a signal that product and engineering leadership need to reset expectations. Sometimes that means re-education, sometimes firmer prioritisation, but always with the goal of reinforcing shared responsibility.

The spine provides structure, but the muscles must still move. If the muscles stop, the whole body weakens.

Where CoEs Belong

Placement matters. A performance CoE belongs in the frontend framework domain, where shared libraries live. A developer experience CoE sits under platform or enablement, improving pipelines and tooling. Accessibility and i18n can sit with design, but must contain engineers who ship code, not only write guidance.

Place each CoE where its work naturally connects to the systems it needs to change.

Lessons from Others

Other organisations have already confronted this tension. Amazon is known for two pizza teams, but those teams sit on top of a thick layer of central services. AWS formalised this with Cloud Operations and Platform Enablement (COPE): product teams run what they build, but platform teams provide secure defaults and reference architectures (AWS COPE). The lesson is clear: autonomy only scales when central teams make the deep, hard work repeatable.

Atlassian has reached a similar balance. Their engineering handbook describes “radically autonomous, aligned teams,” showing how autonomy is possible only when underpinned by shared systems and practices (Atlassian Engineering Handbook). Their public Team Playbook codifies these practices, creating paved paths that give squads freedom without fragmentation (Atlassian Team Playbook).

The UK’s Government Digital Service offers another example. The GOV.UK Design System is often held up as a model of federated contribution. Yet it only works because a small central team curates contributions and fixes issues directly (GOV.UK Design System). Without that spine, the design language would fork endlessly.

Nathan Curtis captures this point directly in The Fallacy of Federated Design Systems. His argument is blunt: a purely federated model is a fallacy. When responsibility is spread thinly across busy squads, invisible work stalls. Contributions are valuable, but they only flourish when a central team carries the core.

Research points in the same direction. McKinsey has written about the “product and platform operating model,” showing that the highest performing organisations explicitly invest in enabling and platform functions alongside product squads (McKinsey on product and platform models).

Each of these cases carries the same lesson. Federation works best when it is anchored by a staffed, central team that takes responsibility for the deep, systemic problems. Autonomy thrives, but only because a spine exists to hold it together.

Rules of Thumb

- When neglect risks creating invisible debt that later explodes, it may be better placed with a Centre of Excellence.

- When variation across products genuinely adds value, it is usually best left with the squads.

- When the work is best spread through stories and peer learning, a guild or inner sourcing can be enough.

- When a problem demands sustained expertise, broad coordination, or structural refactoring across the codebase, it often belongs with a Centre of Excellence.

- When benefits are invisible in the short term but compound over time, a Centre of Excellence can carry the work until squads catch up.

- CoEs work best when placed where their efforts naturally connect to the systems they need to change.

- Stewardship should not mean substitution. CoEs may need to fix the hardest problems, but responsibility should still return to squads.

- If neglect repeats, it is more a signal of a leadership challenge than of a CoE challenge.

Completing the Model

The product operating model has transformed how software is built. Squads, durable and autonomous, are a better unit of delivery than the projects and programmes they replaced. But the model was never the whole story. It describes how to deliver features, not how to sustain performance, pipelines, or developer experience at scale.

What is needed is not a rival model but a completion of the original. Squads at the core. Guilds and inner sourcing to share practice. Centres of Excellence as the spine that provides structure and clears the blockages no one else will.

That balance keeps design honest, pipelines unblocked, reviews flowing, apps fast, and outcomes resilient. Some of the hardest problems will require research as well as delivery, and that research is part of the work. Action clears blockages, but deep thought reveals new patterns. The product operating model does not need defending. It needs finishing.